American economy, part 3

Continuing yesterday’s post—

As with America’s underlying wealth, our residuals of inheritance from labor successes enable the national economy to keep going the way it’s going. They enable most of the middle class, the bottom 90 percent of the population, to survive without our having to address huge harms such as regressive taxation. To call these immense resources and assets a problem is paradoxical, as with supply in supply-and-demand, but they are a fact of American life.

Making thermostats

Take some of the most homespun examples of belt-tightening. That Americans won’t do this, won’t put up with that, and are aficionados of gas-guzzling cars, for example, is often tossed out as a political given in economic discussion. Generally this line of thought is used to justify regressive and damaging economic and social policy, or lack of policy. Thus, like assertions that Americans are turned off by politics, by the duties of citizenship and by political debate, it is heard often from the noise-machine right and from GOP congress members. Regrettably, some of the more over-promoted ‘liberal’ commentators in media also use it, typically the same ones who promote the ‘close election’ and ‘divided electorate’ memes. More on that later.

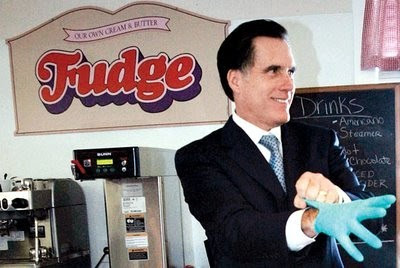

Prospective GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney

Actually, it is staggering how much belt-tightening is already taking place in this land of abundance. And in spite of all our problems—the land of abundance is also the land of waste–a staggering growth in environmental awareness and organic health awareness is also taking place.

Home vegetable garden

One problem here, up top: Unfortunately, most of the burden has been placed on the shoulders of individuals and families. Too little of the effort in relative terms has been shouldered by corporate America and by multi-nationals, too much of it by individual households. No surprise there: This, in a nutshell, is the outcome designed by all that GOP hype about the national debt, about ‘big government’ and about ‘regulation’. No asking big business for anything, no limit on what can be squeezed from private citizens. Even our most strident right-to-lifers in office do nothing to prevent, for example, chemical abortifacients and chemicals causing birth defects from being released into groundwater and the atmosphere.

Policy, meet consequences

Take that matter of the national debt. Set aside the obvious point that the GWBush administration gave us a trillion-dollar war and trillion-dollar tax cuts for the wealthy and for corporations. Set aside that current GOPers in Congress have resisted even the slightest correction for these excesses. Just look at that metaphor of the household budget that GOPers in public office are so fond of—the line that typically starts, ‘Every family knows that if you live beyond your means . . .’, accompanied by metaphors of ‘mortgaging your family’s future’ or ‘loading your children/grandchildren with debt’.

Let’s note some quick points about that household-budget analogy.

1) As we know, the biggest household debt is typically mortgages, college education, or credit cards. A house and a college education are not considered luxuries or riotous excess. These are typical and reasonable outlays of family income, for a considered purpose. Eliminating these kinds of debt would reduce some numbers on a page—but would also reduce shelter and education. It might be added that much household debt also stems from medical necessity—health care—and we’ve seen how much the GOP is attuned to reducing that kind of debt.

2) These categories of debt figure in when household debt-to-income ratio is being calculated. It’s debt-to-income that makes the difference, not debt in isolation. Never—so far as I know—is there an assumption that all the debt has to be paid off at once. Debt-to-income, as the term would imply, compares ongoing yearly/monthly outgo to ongoing yearly/monthly income. But Republican talking points tend to represent ‘debt’ as if all of our national debt had to be paid tomorrow, which is false. And the debt talking point omits revenues. It’s never debt in the context of what you need and what you can afford. It’s always debt as the whole picture, with the false implication that unaffordability is a given. This, to use the household analogy, is like budgeting by leaving your income out of the picture, looking only at your outgo, with a starting assumption that it is somehow normative for households not to spend anything at all. Maybe the core assumption is that it would be better just not to have a household at all. Maybe this is the deep structure or unstated rationale for the whole attack.

3) This disingenuousness has a purpose. As we know, the same members of Congress who do not talk about what we need, what we want for our country, and how to afford it also adamantly oppose any progressive taxation for the wealthy and for corporations. I don’t know of any household where only the kids’ allowance can be used to pay off debts. But this is the effect of GOP policy, in the GOP analogy: Disproportionately, the burden of paying for everything is shouldered by the population less able to pay. As written previously, GOP tax policy mainly boils down to this central aim—shifting the tax burden from the wealthy to the middle class, from corporations to individuals, and from the federal government to states and localities, which generally have more regressive taxes.

(Side note: GOPers so concerned with loading our grandchildren with debt show remarkably little concern about conservation. Don’t they want our grandchildren to have some oil left?)

Oil tanker headed overseas

Back to the future—

By any reasonable measure, U.S. individuals and households have made sweeping changes over recent decades. To use a few easy examples from transportation:

- Millions more people drive smaller, more gas-efficient automobiles than previously

- Use of mass transit is up in regions where it is available

- Millions of people plan local trips and errand runs on the UPS model, combining tasks and planning routes so as to eliminate unnecessary driving

- Millions of households are using online shopping and delivery, as shown by business for UPS and eBay among others

- More expensive travel is being replaced by shorter trips and by ‘staycations’

- Buying locally where possible is increasingly popular, including buying local produce

- Home gardening continues to rise, bringing food supply even closer to home

- Even the chickens are coming home to roost, in some areas

All of these are individual small changes on an immense scale, given our population of over 300 million. None of them, so far as I know, have been accompanied by massive social dislocation or even widespread unpleasantness. Some congress members may vilify Amtrak, but most people seem to recognize that there’s no percentage in making commuting or travel less feasible for the already-congested East Coast.

Regrettably, individual changes go only so far. Mass transit is a boon to people who have it, but not every region has it. Metropolitan Houston, Texas, for example, with an immense population and land area to match, is only now moving into light rail. The planners actually ripped out miles of railroad track west of town, to expand double-decker freeways. The track was ripped out because it ran parallel to—next to—the freeway. In other words, it could have been used for passengers, for commuting.

Commuting to work is still the big gap in improving traffic and energy conservation. Millions of miles of roadway, every weekday morning, in virtually every metropolitan area, fill up with one-passenger-per-car traffic. The daily commute to work, after all, is one place where purely individual trip-planning and energy conservation do not provide an adequate solution—people have no choice about going to work, and little choice about how to get there. Too little mass transit, too little company-provided transportation, too little company-subsidized moving so you can live near where you work. Instead, GOPers around the country are cutting mass transit in public budgets—and finding ways to hike taxes on individuals who benefit from mass transit, however modestly: raising fares and parking fees, taxing employer subsidies of every sort, and reducing federal contributions to cash-strapped states and localities.

Too little consistent treatment of and attention to neighborhood schools, too, so that fantastical differences among neighborhoods can be corrected or ameliorated, but maybe that’s a different chapter.

More later