The American Economy, part 2

Following up on last week’s post–

We are all inheritors of the labor movement

Another fundamental of the U.S. economy is one that we have had for more than fifty years: We are all living on a gigantic store of assets, workplace conditions and industries produced by the American labor movement from the 1930s through the 1970s. This fundamental fact remains even in the historic economic slump from the mortgage-derivatives debacle. Despite the decline of labor unions and despite even the unthinkable wealth disparity between top and bottom in our economy, our middle class is still living on residuals of wealth and productivity from the earlier labor movement. The ‘boomerang’ phenomenon—young adults moving back in with their parents, because their parents have houses with space for them to live in—is only the most obvious example. This fundamental is not just a matter of inheritance in the limited literal sense of inheriting the parental house, a car or two and whatever is left in the family’s checking and savings accounts, etc., after end-of-life medical bills. It is a matter of being able to go to work with a reasonable expectation of a paycheck, a defined workday and a defined workweek with a weekend or other days off. It includes extensive nationwide use of ports, highways, public schools and public services that we tend to take for granted. And it is a matter of successful social programs brought about by the New Deal and the fight of the labor movement on behalf of the middle class—Social Security and Medicaid, which moved America’s elderly population out of the poverty column from the middle of the twentieth century onward. And it includes an incalculable amount of intellectual capital, much being donated or at best going for under market value in the nation’s universities, mass media and publishing.

Post-war housing

The amount of wealth that the majority of ordinary people have inherited from past labor becomes clearer when one thinks about inheritance in the more limited sense, as in housing and the giant second-hand market in the U.S. The overwhelming majority of individuals post-World War II in this country did not grow up thinking of themselves as heirs and heiresses. The exceptions who did grow up thinking of themselves that way—figuring out how much they stood to inherit in due course—did not necessarily benefit from the perception. It can be a disincentive to good work. Nonetheless, the amount of wealth being quietly passed along by inheritance, one way or another, to people not yet senior-citizen age in this country is staggering. It isn’t written about much—most people don’t want to talk about it, for reasons ranging from grief and mourning to simple self-protection—but it is one of the reasons why so much of the American middle class can make ends meet even in a time when this country’s wealth inequality approaches that of Sri Lanka.

Two-carat diamond engagement ring

Some specific examples of inheritance in the limited sense, in order of generally ascending value:

- House contents. Admittedly, a stack of empty plastic margarine containers for left-over food—hoarded by thrifty post-war parents to keep from having to buy that expensive Tupperware—may not look like a treasure trove. But the total cost of all the tools, kitchen and garden supplies, clothing, furniture and ‘miscellaneous household’ would mount up fast if purchased simultaneously, even in big-box discount chain stores. People who inherit a household of items keep them, give them to younger relatives, sell them–on eBay, at yard sales, or at auction–or donate them to charity. The thrift stores in metro areas burgeon with aids to social mobility for legal immigrants and others less likely to have inherited the equivalent supplies. As with yard sales, auctions and sometimes eBay, marginalized buyers are getting the most price-elastic goods at a discount. And an additional benefit of Keep using, Re-use, Recycle is, of course, that it keeps the stuff out of landfills. As in the household Tip O’Neill grew up in, described by Jimmy Breslin in How the Good Guys Finally Won, nothing goes to waste.

- With some exceptions such as unsafe baby beds, house contents are the innocuous, Mamsie-Pepper side of inheritance. Diamonds are pretty much the obverse side of inheritance. Let’s note first that most diamonds are not very valuable. Any diamond less than a quarter of a carat should not cost much, and the price of a piece of jewelry set with many tiny diamonds—under 0.25 carat each—should reflect only a multiple of that individual price, skilled labor and the gold aside. Even with larger diamonds, the wholesale price is going to reflect the quality of the stone, meaning clarity and color (colorlessness), and the overwhelming majority of diamonds are not D-E VVS-IF; nowhere near. That said, someone with a solitaire diamond purchased more than five years ago—let alone thirty or more years ago–might have an asset, if s/he can get it graded accurately–not ‘appraised’, but graded for color, clarity, cut and weight. Two- or three-carat diamonds of top color and clarity are going for astronomical prices, bigger ones for even more. Regardless of whether diamonds are ‘the new gold’, as the New York Times recently suggested, good solitaires have near-immediate cash value. I am intrigued that seemingly few banks and other mortgage lenders have taken them in exchange for a mortgage balance. A six-figure diamond has got to be worth more than a risky outstanding loan (lender), and switching the genuine article with a good simulant or a white sapphire seems like a small price to pay for getting out of debt (borrower). Maybe it’s happening and they’re not talking about it.

- Houses and land are among the most obvious inheritable assets, and tend to be written about the most comprehensively. Many articles are published in the business press, in consumer blogs, and elsewhere about the pitfalls in inheriting a house, the possible tax liability—not large, for most people—or about options for what to do with an inherited house. A modest house in a post-war tract development is not the immense treasure that many people may have imagined during the housing boom. But if the house is sellable at all, given condition and neighborhood, obviously it can generate cash to offset a car purchase, college tuition, etc., or to build a rainy-day fund. A bigger windfall could pay down or pay off descendants’ mortgages—nothing to sneeze at, if you value your health and would benefit from reducing stress in your life. Multiply that by a few million, and you’ve got something with real impact.

- Life insurance policies are among the last few reasonably good deals in the private insurance market. It’s interesting how vague and moderated the ads for life insurance policies tend to be; looks as though the rest of insurance—health, disability, malpractice—has frowned down anything that would highlight contrasts. Back to inheritance—any parents who purchased life insurance policies at a reasonably young and healthy time of life managed a boon to their offspring, pretty much uncomplicated by tax or other liabilities.

- Et cetera.

The collective amount of just the above-mentioned specific assets is virtually incalculable. On a macro scale, these assets are what enable so many in our population to survive while underemployed. Just the collective assets involved in home gardening for food production, and for home improvement, contribute significantly to the national economy. However, as mentioned, our national inherited wealth far exceeds the limited, literal kind of inheritance sketched here.

University of Michigan

We have inherited industries, farmland and natural resources including (for now) potable water. We have inherited universities, museums and a vast communications system, an immense intellectual infrastructure. We have inherited a national physical infrastructure with the potential for improvement that would also ‘put people back to work’, as candidates for office keep saying while refusing to do so.

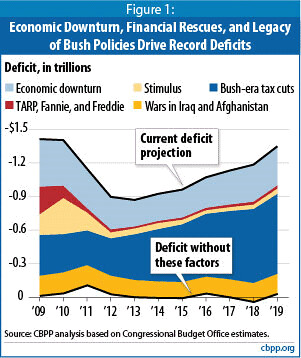

Current mouthings of GOP politicians and their television shills about ‘jobs’ and ‘unemployment’, fed into media outlets for the election, do not acknowledge our immense inherited wealth. To do so would acknowledge the importance of American labor, and would acknowledge the necessity of regulation (law) to safeguard natural resources and human lives. No one on their side of the line points out that a country of our resources and assets has the capability, for example, to educate all its youth. Quite the contrary: When President Obama suggested that everyone who wants to go to college should be able to, Rick Santorum called him a “snob.”

This wasn’t mere campaign rhetoric, stupidity and mean-mindedness. Santorum and his ilk jumped on Obama’s case because, from the perspective of GOP candidates for office, the reminder that we have immense assets for education is dangerous. Once it is recognized that we can educate our population, after all, the inevitable question becomes why don’t we? We have more than enough resources and assets to provide for our health needs, too, and look what happens when someone tries to do so. Aside from what notable newspapers like the Washington Post did to health care reform, the supermarket tabloids are vile, even beyond their usual hysteria, in attacks on first lady Michelle Obama in the context of health–beauty or nutrition, exercise or fashion.

There is danger in the reminder that the U.S. has immense assets–for health, for nutrition, for music and the arts; for national parkland, our coasts, mountains in West Virginia, clean water in any river, lake or aquifer. You name it; if someone brings up or indirectly reminds the public how genuinely wealthy this country is, the rightwing noise machine gets hot to trot.*

More later

*An individual heartening exception: David Koch, to do him justice, recently donated $35 million to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. My view remains that the wingers funded by the Koch brothers mostly take from, rather than give to, the public. But this is going in the right direction.