Only two of the books in the library in Jane Austen’s home were published in 1803. In hindsight, Austen’s family may not have considered 1803 a very good year for literature: that was the year of Austen’s infamous first success, when a publisher bought her anonymous two-volume novel Susan, for ten pounds–and then sat on it for the rest of Austen’s life.*

There are some ironies in the fact that Austen now graces Britain’s ten-pound note; she rarely saw ten pounds herself.

UK new ten-pound note, 2017

One of the 1803 publications was Poems on Various Subjects, by Scots author Anne MacVicar Grant (21 February 1755 – 7 November 1838).* Today is Grant’s birthday.

An homage to both nineteenth-century women authors would note that Jane Austen took a continuing interest in the writing of Anne Grant. In a letter dated 21 February 1807, Austen jokingly recommended Grant’s published letters to her sister Cassandra “as a new and admired work,” clarifying that she had not read them herself and knew nothing about them. (These references found in Deirdre Le Faye’s authoritative edition of Austen’s letters.) On 11 January 1809, the family was reading Grant’s Memoirs of an American Lady, though with mixed feelings. (Scots-born Grant had grown up in Albany, New York, then returned to Scotland with her family.) In February 1813 she lent a three-volume work by Grant to a family acquaintance. She also bought Anne Grant’s poems.

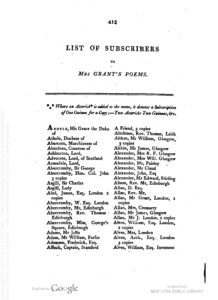

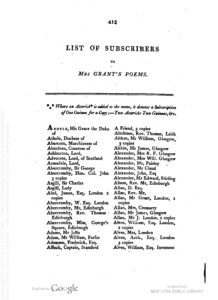

Mrs. Grant’s subscriber list

Anne Grant herself did well in 1803. Books were often published with the help of subscribers (crowdfunding), gathered beforehand, and Grant raised quite a healthy list. She was already a successful author–good thing, since she and her family needed the income.

In my scenario, Austen culled Grant’s subscriber list for character names–fictional characters, actual names. Call it an Austen-themed parlor game: Grant’s book with the subscriber list is accessible online, full-text, digitized by Google (originals in U Michigan, NY Public Library and elsewhere); free to test it.

Obviously these would be individuals of a certain literary caliber–people capable of appreciating Grant’s writing and willing to underwrite it with a modest advance, and willing to have their names printed at the back of the book in a 33-page list. (A few subscribers are anonymous, and the list includes at least one book club.) They would also be men and women not averse to their surname’s appearing in a book, since it just did. Austen’s little joke.

Thus the list features some members of the nobility, but only some; predictably some relatives of Grant’s; and a hefty, not to say dominant, proportion of Scots. Grant was born in Glasgow, and after her family’s return to Scotland lived and worked in Laggan, Stirling, and Edinburgh.

WARNING: only fans of Jane Austen’s novels should read on. Take the novels one by one and cross-check Grant’s subscriber list for character names.

This excludes Northanger Abbey, originally named Susan, which Austen had finished and revised in 1803. When someone else published a novel titled Susan, she re-named her heroine and re-titled the book (Catherine); her brother and sister brought it out, re-titled again, after her death. (Critic Ian Sansom got this wrong in TLS. While Austen was concerned about finance, pay, and book sales, she was not the one who chose the title Northanger Abbey. It was Henry Austen and perhaps Cassandra Austen who targeted the ‘gothic’ demographic by putting the abbey into the title.)

Note: Sense and Sensibility is dealt below; scroll down.

Moving on instead to the other famous Austen novels–

Pride and Prejudice. (remember your character names here)

⊂ ON the list: Bennet. (We knew that; Mr. Bennet is a great reader, and Elizabeth is accused of being one. However, there is no female Bennet on the list, only some Mr. Bennets. Btw do we ever learn Mr. Bennet’s first name in Pride and Prejudice?) There are subscribers named Forster and Millar (colonels in the novel, past and present), and several named Hill, like the Bennets’ sensible housekeeper, evidently a representative of upward mobility as well as of appropriate behavior. A Miss King. Maybe Mary King had more time to read, and/or more disposable income or pocket allowance to spend on books, after she escaped the clutches of Wickham. Speaking of whom . . .

⊂ NOT on the list: notorious rogue Wickham. Unlike fellow rogues John Thorpe and Willoughby in the earlier books, and Henry Crawford and William Elliot in the later, Wickham does not refer to poetry or novels. Also not on the list: Bingley. There is no Mr. or Miss Bingley–remember Caroline Bingley’s picking up Volume II of the book Darcy is reading? No Mr. or Mrs. Hurst. (There’s not even a Mrs. Bingley; Jane Bennet may read less than Elizabeth, especially after she marries Bingley.) NO Mr. Collins–remember Mr. Collins’ picking up a large folio and talking instead of reading? No Mrs. Collins, before or after marriage; the surname Lucas is also not on the list. More surprisingly, no Gardiner, despite the Gardiners’ taste and intelligence. (Mr. Gardiner may be too busy with business and Mrs. Gardiner with family matters.) No Mr. or Mrs. Phillips, either. (Uncle and aunt Phillips? Not likely.) On the other hand, the bluest blood in P&P is also conspicuous by its absence: the names Darcy, Fitzwilliam, and De Bourgh are not on Grant’s subscription list. (The pompous, ill-bred Lady Catherine’s absence is not surprising. Perhaps Darcy and Fitzwilliam are anonymous subscribers.)

Mansfield Park.

⊂ ON the list: Crawford. The flawed Henry Crawford and Mary Crawford are smart readers. Bertram. Naturally: the house has a fine library, and everyone in it reads, except Lady Bertram and possibly her pug dog. Grant. –Anne Grant’s relatives contributed as subscribers; but surely the Reverend Mr. Grant in MP was a reader as well. Fraser. Yes–including “The Honorable Mrs. Fraser, London“–like Mary Crawford’s discontented bird-in-a-gilded-cage friend. (Is this one of Mrs. Fraser‘s complaints? –that her wealthy older husband, proud of a fine library, wishes her to read more? Or to support authors, but without sleeping with them?)

⊂ NOT on the list: Price. Odd; no one would expect Mr. and Mrs. Price to be readers, but Fanny Price has steeped herself in reading. However, her name changes when she marries. Rushworth. –No Rushworth on the list. (Again, not a surprise.) Yates. The baron may be more interested in scenery-chewing than in reading. Norris? I bet myself that Mrs. Norris’ name would not appear in a list of book subscribers, given her lack of literary bent and her marked aversion to spending her own money. I half-won: no Mrs. Norris, but some Mr. Norrises.

Emma.

⊂ ON the list: Campbell. Cf. “my excellent friend, Colonel Campbell,” the man who didn’t give Jane Fairfax the piano. (There are many, many Campbells on this Scots list). There is also many a subscriber named Brown (a better name in Scotland than in Hartfield). There is also a Mr. Dixon, though no Mrs. Dixon. (Enough said.) The name Martin is also on the list–score another point for the upwardly mobile. Remember the ball scenes, before and during the ball? –There are two Gilberts on the list, an Otway, and a Mrs. Cox.

(N. B. This list of subscribers is not being seriously presented as the sole source for so many Austen character names. In Emma, for example, the ball scenes would give Austen a perfect opportunity to gratify requests from locals to have a character named after them, in a cluster, without interfering with the story line.)

⊂ NOT on the list: Elton? –Surely you jest. Mr. Elton is too busy rich-wife-hunting to read. No Miss Hawkins, either. (No surprise there.) No Suckling, whether Mr., Mrs., or Miss. Few of Mrs. Elton’s friends make the cut–there is no Jeffereys, Partridge, Milman, Smallridge, or Bragge. (Austen’s names get a bit unsubtle in connection with Mrs. Elton.) A bit more surprisingly, no Miss Bates, and no Mrs. Bates. But then Miss Bates and her elderly mother probably cannot afford to subscribe. As to the most prominent names in the novel, all are missing. There is no Woodhouse on the list, although there is a Woodhouselee; conversely, there is no Knightley on the list, although there are several subscribers named Knight. (Knight is also a surname in Austen’s family tree, and very close to home; one of her brothers took the name.) No Fairfax. No Churchill.

Persuasion.

⊂ ON the list: Elliot. –Certainly. Persuasion, like Northanger Abbey, is very much about books, and Austen plugs other authors in it; the lovely Anne Elliot is a reader both natural and cultured, and even her sister Mary gets books at the circulating library. Dalrymple is on the list–presumably a dignified family willing to emblazon the list to benefit the author. Smith. Contradicting Sir Walter Elliot’s snobbery–“Mrs. Smith, such a name!”–several subscribers with the ordinary name of Smith do appear. Also, Byron is on the list of subscribers–a “Miss Byron.”

⊂ NOT on the list: Mrs. Clay. –Not a chance. Mr. Shepherd. (However, there is a “Miss Shepherd.”) No Croft, no Wentworth, no Harville. Sorry to say, their many virtues do not extend to underwriting books; maybe 1803 was before their promotions or retirement would enable them to do so. And the younger Captain Benwick, lover of morbid and lachrymose poetry? –No. No Carteret, either. No Musgrove.

This short exercise is tongue-in-cheek. All of Austen’s character names have multiple (possible) sources. I think, in fact, that Austen made a point of literary thrift, or literary multi-purposing. One could call it great art; a person, place, or thing does not feature in Austen’s novels for only one reason. This is not only a matter of sources and analogues.

However, a surprising proportion of the time, this little game works. If a character’s name (after 1803) does not appear on Mrs. Grant’s subscription list, the character turns out to be less than a genuine reader.

Fans of Sense and Sensibility may notice that S&S is the exception. –It would be ridiculous to argue that Marianne Dashwood is less than a genuine reader. But if Austen as a struggling author looked at one list of subscribers, she looked at more than one. And as it happens, another list came out in 1803. The Catalogue of the Brompton Botanic Garden, published by Bulmer and Co., Cleveland Row, St. James’, contained a “List of the Subscribers to the Brompton Botanic Garden.” This shorter list includes Dashwood, Willoughby, Palmer, Williams, Mrs. Smith, and the Earl of Morton. No Allenham–but an Allen immediately follows an Ashburnham on the list, a tempting vanity-bait to Austen’s fondness for jumbles or anagrams.

(Even place names can be part of the game. The evocative Cleveland, in the publisher’s address, resonates powerfully with Marianne Dashwood in S&S. Cleveland Row and nearby Cleveland Court, around the corner, also had real-life importance for the Austen family.)

Checking the list, checking it twice, to see who’s naughty or nice, or at least literate, works again.

*The other was the six-volume Female Biography, by Mary Hays. Both by women, although there’s more to the story than that.