Veterans Day, 2013

It would feel strange to wish someone “Happy Veterans Day.” Not that I don’t think of the veterans I know best on Veterans Day, but I think of them on many other days. My father was in the Army for almost five years, in World War II; his older brother was in the Navy; his younger brother was in the Air Force, or rather the Army Air Corps (17th Bomb Group, 34th Squadron). Land, sea, air. My grandparents were exceptionally lucky: all their sons and sons-in-law served in World War II, and all came back safe, setting aside the bout of malaria my father contracted in a New Guinea jungle. He came home weighing 130 pounds, at almost six feet, but he and my uncles were not critically wounded.

New Guinea

Funny the little misconceptions we can grow up with. For years, I thought my late father had dashed out to enlist after Pearl Harbor, as I said to friends, and wrote. Actually he dashed out to enlist before Pearl Harbor. His East Texas family followed the news, followed world events as well as they could, and had a strong interest in history. His parents later owned and operated a little newspaper in their tiny hometown. My father himself owned one for a year–something I did not realize until much later, since I was four years old at the time. I do remember my mother saying, maybe literally, that his linotype operator made more than he did. He believed in paying employees.

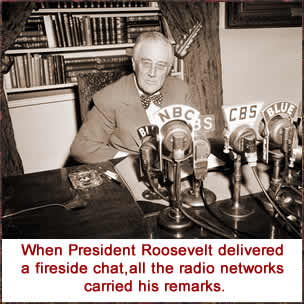

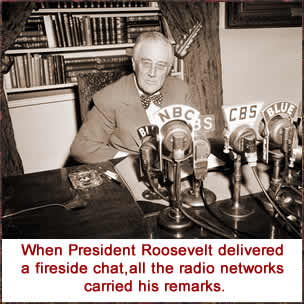

FDR by radio

In any case, the family followed the news on the radio, in newspapers, and in the community, in the era of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and the New Deal. They were civic-minded; my dad’s pet cat, when he was growing up, was named Enum, as in the old voter rolls (enum.). They were pretty well aware, or as aware as reporting permitted, of events stirring in Europe.

Britain and France formally declared war on Germany September 3, 1939–the day my father turned seventeen. His is not one of those stories about a kid falsifying his age in order to enlist, like fellow Texan Audie Murphy, but he surely felt that his mission was in the cards, and having been double-promoted, he graduated from high school early, going on to a term or two of college before joining up, once he was legal.* He was put into Third Radio Intelligence Company, U.S. Army Signal Corps.

The company was pretty new at the time. Major J. S. Harley, author of Reading the Enemy’s Mail, says that

“In October 1939 the Third Radio Intelligence Company, one of the first tactically oriented radio intelligence units, was activated at Fort Monmouth. A cadre of eleven men, plus one recruit and an officer, formed the nucleus of the company. By November the company reached full strength and began an intensive four week training program. The problems the unit faced in training would beset new units throughout the war.”

A year later, by the time my father joined, the presumably full-strength unit was at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. My parents’ old papers contain printed menus for a special Thanksgiving dinner and Christmas dinner celebrated by the company at Fort Sam Houston, bound with embossed covers, tied cords, and a frontispiece-type tissue over the menu page. My father’s name is on the guest list for Christmas dinner in 1940, between Jack J. Bridwell and Darrell J. Cagle, under Oliver L. Blumberg and above Leon C. Calley, with several other Johns and Jacks. His name is not on the list for Thanksgiving that year (November 21); he may have entered the company after the menu went to print. Thanksgiving dinner began with shrimp cocktail and oyster stew and went on to turkey and ham, followed by fruit cake, pies, punch, ice cream, fruit, and cigarettes (included on the menu). Christmas dinner was less extensive, though it again began with oyster stew and ended with cigarettes. Those may have been the best meals they ate for five years, those who survived the next five years. The menus themselves were probably the dressiest documents owned by most of the young guys in the company, aside from their recent high school diplomas.

Nazi movement

Beyond any doubt, John W. Burns joined the army to fight fascism. Although he did not talk about bloody war experiences to his children, his views on fascism and Nazi Germany were abundantly clear. However, the anecdotes he shared with immediate family, in front of the children, were the non-grisly experiences. There was the time on a stop somewhere in Europe when the troops were privileged to hear a great opera singer. As my father told it, the story was that the troops had been promised entertainment, and when the singer appeared–an older woman, not glamorous, not a pin-up girl–there was some disappointment, maybe a little cat-calling and sarcastic wolf-whistling. But when she opened her mouth, as my father put it, the most ignorant guy in the place knew that this was the greatest voice he had ever heard, and when she finished, they gave her a standing ovation.

The Susan Boyle experience, sixty years earlier.

Then there was the time some of the guys, by that time in the Pacific and on shore in Sydney or another Australian city, decided to go horseback riding. Where the horses came from I do not know, but the short story is that the horse my father got on–with his scant riding experience, drawn from farmland in East Texas, not a ranch in West Texas–turned out to be a retired steeplechaser. So the horse galloped off, jumping fences and ditches, careening down the streets, and some local called out, British-style, “Stop that animal!” with my father thinking something along the lines of I wish I could.

I also remember my father saying he learned to play chess in the army. As he put it, a Jewish guy from New York, in his unit, noticed that he was smart, and ‘made him’ learn to play chess so he would have somebody to play with. (Spread the pronouns around, divide them up, and distribute them equitably.) He was pretty good, especially for someone who did not play regularly (good enough so that when he happened to walk through the living room where my child and I were playing chess, years ago, he quickly gave my son enough tips to beat me).

Only at the time of the funeral, and from his brothers, did I hear the other anecdotes.

As the chances of war went, my father was not sent to Germany; he was sent to the Far East (this is the Army). One stint was in the Philippines, on which his perspective was that the Filipinos loved American soldiers, who would give them things–a penny, a cigarette, a stick of gum–but detested the British, who would try to force them to shine their shoes or do odd jobs, in a final reductio ad absurdum of waning colonialism. The view may have been a bit idealistic, but setting aside the natural chauvinism, he appreciated the Filipinos’ desire for independence and their trust in America.

Philippines today

There was the stop-over in Australia en route, including the horse outing. He spent long months in New Guinea, with a lot of time spent by the troops wondering when they would get to go home, and whether they would get medals, or promotions, or pay hikes, as they heard other troops did. At some point the troops received a big crate of books, sent by kind souls back home, and my father later said with pardonable hyperbole that he read every great book ever written, in six months, in the army. He mentioned specifically Huck Finn, and Dostoevsky’s passage about how even a man stranded alone on a narrow mountain ledge, in miserable conditions, would cling to life. (The passage may have struck a chord.) There was still enough to do, and to witness. One day–according to my uncle–my father was walking through the jungle, by himself, and rather suddenly walked out into a clearing. At the same moment, a Japanese soldier entered the clearing from another direction. The Japanese soldier gave a single horrified look at the young American, pulled out a grenade, and blew himself up with it.

I do not know exactly which year the incident occurred. My impression is that it was close to the end of the war. I do know that it was not dinner-table conversation. My father may have told his parents, after he got home, and certainly told his brothers, but neither he nor anyone else dwelt on it aloud.

In memoriam: John Wilson Burns (September 3, 1939 – July 7, 1997)

*Added Nov. 12:

His Honorable Discharge paper shows “date of enlistment” to be 5 Sep. 1940, two days after his eighteenth birthday.

“Decorations and citations”: Asiatic Pacific with Bronze Star; Distinguished Unit Badge.