Halliburton, Cheney and the Bush administration in Iraq: 2003

Vice President Dick Cheney

This history is intended as summary and a reminder for anyone who might wonder why connections between former Vice President Cheney’s Halliburton, Inc., and subsidiaries and the George W. Bush administration matter for Iraq. The key facts were not widely reported to the public, or with adequate focus and emphasis, when they would have been timely during the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, and during the first two years of the Iraq war.

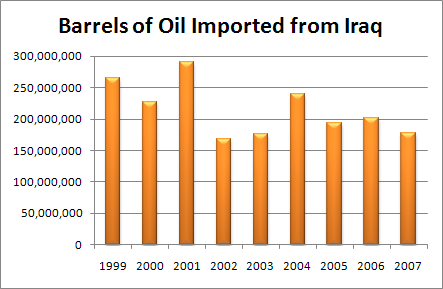

To begin with, under the second Bush administration the U.S. had a trade deficit with Iraq: In other words, while top administration figures were inveighing against Saddam Hussein, the administration’s oil-industry donors and staunchest supporters were quietly running up record oil imports from Saddam. Until May 2003, the U.S. imported more goods from Iraq in regular commerce, even while preparing war against it, than exported to it. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Division, in January through June 2003 the U.S. imported $2,516,700,000 worth of products from Iraq. During the same period it exported $30 million worth of products to Iraq, for a trade deficit of about $2.4 billion.

UK consulted Big Oil before invading Iraq

That’s a lot of doing business with the devil.

In 2002, the U.S. trade deficit with Iraq was $3.5 billion. For 2001, our trade deficit with Iraq was $5.7 billion: We exported $46 million worth of goods to the Iraqis and imported $5.8 billion worth. Interestingly, our trade deficit with Iraq actually peaked in election year 2000, at $6 billion, a fact not emphasized on the campaign trail by those evil-doer-haters George W. Bush and Dick Cheney.

The previous U.S. trade surplus with Iraq lasted through 1996.

U.S. oil imports from Iraq

Perhaps this should not be surprising. Major U.S. industries, like the oil industry to pick a random example, have done large-scale commerce with the strife-torn Middle East for decades. Our trade deficit with Iraq was dwarfed by our trade deficit with Saudi Arabia, with whom we last had a trade surplus in 1998. Our monthly trade deficit with ally Kuwait almost doubled from 2002 to 2003. (Needless to say, the U.S. consistently runs huge trade deficits over-all, our #1 trade deficit partner being China.)

Given that the second Bush administration invaded and occupied Iraq, it is a good idea to remember the extensive U.S. commerce between Big Oil and that pitiful nation.

According to those bruisers at the Census Bureau, by some strange chance Iraqi imports fell into the single category of “mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials,” i.e. oil. From January through April of 2003 we imported hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of oil from Iraq, with imports nearly doubling in February and March, when the invasion took place. Then in May 2003, at the height of the direct invasion, our Iraq imports dropped to $80 million, still a trade deficit. In June 2003, U.S. imports of Iraqi oil fell so far that, for the first time since 1996, the U.S. had a trade surplus ($8 million) with Iraq.

U.S. oil companies, in fact, were consistently Saddam’s biggest customers. In 2001, the U.S. was “the main market for Iraqi crude,” according to the Middle East Economic Survey. Forbes estimated that U.S. companies purchased 70 percent of Iraq’s oil in 2001. One of the single biggest U.S. customers was Chevron, where Bush’s National Security Adviser and second Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was an executive. Chevron merged with Texaco less than a month after the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the merged giant ChevronTexaco continued its purchases of Iraqi oil, with no sign that the White House considered this a security breach.

Not that U.S. exports to Iraq were nonexistent. Our two biggest categories of export to Iraq in 2002, by far, were “drilling and oilfield equipment”–$16 million–and “excavating machinery”–$4 million. That would be Halliburton Company, headed from 1995 to 2000 by Richard Cheney, who left Halliburton to join the Bush ticket in the election.

That’s a lot of selling to the devil, especially considering that Halliburton subsidiaries were basically responsible for restoring Saddam’s oil fields after not one but two wars, the Iran-Iraq War and the first Gulf War. One might argue that Vice President Cheney’s former company was doing what it could to reverse our trade deficit with Iraq. On the other hand, it seems obvious that if the Bush administration had really wanted to know more about Iraq’s supposed ‘weapons of mass destruction’, it could have asked Halliburton. The giant conglomerate produces and distributes oilfield equipment and related services worldwide, including in Iraq. “Parts for boring or sinking machinery” were the second-largest category of exports from Texas, where Halliburton is based, for every year immediately preceding and following Cheney’s transition from the company to government.

Indeed, while Cheney was head of Halliburton, Halliburton subsidiaries were forging ahead in their continuing project of rebuilding and maintaining Iraq’s oil industry for Saddam. Dresser-Rand and Ingersoll-Dresser Pump Company, two Halliburton subsidiaries, had contracts worth more than $73 million with Iraq during Cheney’s stint at Halliburton.

Halliburton, originally founded in Great Britain but subsequently incorporated in Delaware, has more than 500 subsidiaries, including some located in those notable oil-producing nations the Cayman Islands, Barbados, and Bermuda. Halliburton acquired Dresser Industries in September of 1998. During the presidential campaign, Cheney said under questioning that he had a firm policy against dealing with Iraq, but senior company executives handling Iraqi business reportedly did not hear of a prohibition against it.

News reports subsequently revealed that Houston-based Kellogg, Brown & Root, another chief Halliburton subsidiary, received a noncompetitive-bid contract from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2003 to rebuild and repair Iraq’s oil fields. The contract was officially stated as capped at $7 billion but with no official projection of actual costs.

Image problems and imaging

The petrochemicals industry has capabilities beyond well-drilling and extinguishing oil field fires, and Halliburton has other subsidiaries besides Dresser and Brown & Root that could have been relevant to operations in Iraq. In September 1996, Halliburton merged acquired a company named Landmark Graphics Inc, acquiring with it Landmark’s five-year plan and its technological capabilities. The September 9, 2001, prospectus for the Halliburton-Landmark merger reads in part:

“Landmark, together with its subsidiaries, designs, markets and supports sophisticated computer-aided exploration (“CAEX”) and computer-aided reservoir management (“CARM”) software and systems. In more than 70 countries, geologists, geophysicists, petrophysicists and engineers use Landmark products in exploration for and production of oil and gas. Landmark’s applications software transforms vast quantities of seismic, well log and other data into detailed computer models of the subsurface. These models reveal critical information about subsurface formations.”

In simple, non-scientific terms, companies such as these have spent years trying to see underground in places like Iraq, this one in particular.

As we know by now, the myth that Iraq had nuclear weapons had about as much dignity as the one that the late Osama bin Laden was going to fly in on a magic carpet at any moment, white beard flowing in the wind, and sprinkle anthrax dust over some D.C. press briefing. But the WMD myth was particularly brazen in flouting commerce as well as science. With its capabilities, the company would have detected sub-surface testing of nuclear weapons or development of missiles in Iraq, where Halliburton itself operates—literally–on the ground.

The key term is “subsurface imaging.” As its SEC filings describe,

“Landmark is engaged in the business of designing, creating and marketing an extensive line of integrated software applications to the oil and gas exploration, development and production industry for seismic processing, 3D and 2D seismic interpretations, geologic and petrophysical interpretation, including reservoir analysis, mapping and modeling of geophysical information, well log and production analysis, drilling and production engineering and data management.”

So why wouldn’t some subsurface imaging, already used to see underground, even in the desert, have worked in Iraq, to detect WMDs (if any)? The number of reporters in Washington, D.C., who posed this question in 2003 is not legion.

One scientist who prefers not to be named, but who worked for five years with a Landmark director, explains that Landmark’s mega-computing-power software does indeed do subsurface 3-D tomography (imaging). As he explained it, however, the imaging is “based on traditional seismic inputs.” That is, you “shoot a small explosion or use a thumper truck, and capture the echoes with an array of many (can be several hundred) geophones [microphones firmly in contact with the ground]. The echoes are then digitally recorded in massive data files” and processed. The output is then color plotted on wall-size sheets of paper, or on monitors, where geologists can study it. The scientist suggests that this software may not be designed to work with voids–caves, tunnels—or with very shallow formations less than 200 feet down.

What would help would be ground penetrating radar. The U.S. government, he pointed out, has had ground penetrating radar, which can get shallow (less than 50 feet underground) subsurface information, since the sixties and seventies. GPR was used to discover camouflaged missile silos back during the Cold War. The government disclosed this secret capability “by publishing maps of the underground tributaries of the Nile soon after the first launch,” he added.

Military uses aside, ground penetrating radar is well known in the oil business. Geologists use it to find oil. It has also been applied in other fields. Archaeologists have used it to locate dinosaur bones. Its fairly simple process of penetrating the earth with radio waves and then returning the signals to a computer is also used in detective work (forensic tomography), to discover human remains. The basic idea parallels sonograms used in pregnancy.

So again, couldn’t this process have worked in Iraq? – Or, for that matter, to scrutinize underground caves in Afghanistan?

One expert on this matter is Dr. H. Roice Nelson, a geoscientist in the global oil business who founded Landmark Graphics.

“Yes,” he said, the technique could work, “if the data were available.” But, he said flatly, “they’re not.” Data are not available for Iraq and Afghanistan, because no one had done the large-scale seismic surveys. “It would be very expensive.” Remote-satellite technology is always expensive. [emphasis added]

Asked whether the financial cost would be greater than having the operations handled by troops on the ground, he demurred.

“If I had two or three days,” he remarked rather casually, “and got together with other people in the field,” he could probably come up with a good cost estimate for the necessary “large-scale remote,” “air-mag surveys.”

“But I can’t afford to do it on spec.” Did anyone in the administration get in touch with him, asking for volunteer expertise on what lies beneath, in Iraq? No. Nor, apparently, is there word out on the geologist street that others are being approached. If any geologists are contracted, or have been used, to employ these capabilities, there is no sign of it. A big question, obviously, is whether the process would work. Nelson does not predict an outcome but comments that it still might not turn up hidden weapons. In a short telephone interview, we did not discuss the human cost of the effort in Iraq.

He declines to speculate on whether this effort has been made, at all, by the government.

“I read the same news reports you do.” “You might ask Dick Cheney,” he signed off. “He used to head Halliburton.”

Before 2003

For the record, here is some further background on Dresser, Halliburton, and Bush-Cheney:

George W. Bush’s father was George H. W. Bush, 41st president of the United States. The Bush family was from Connecticut, where the elder George Bush’s father, Prescott Bush, was a U.S. senator. Prescott Bush–and this background was not reported during the 2000 election cycle—also was on the board of directors of Dresser Industries from 1930 to 1952. A director for twenty-two years, Prescott Bush was Dresser’s longest-serving director, according to David A. Smith.

Dick Cheney, while CEO of Halliburton, agreed to acquire Dresser Industries in 1998. Dresser had just acquired M.W. Kellogg, which subsequently merged with Houston firm Brown & Root, becoming Kellogg Brown & Root and then KBR. As everyone attuned to politics knows, the Bush team was already gearing up for the White House run at the time. This is one of those sequences that makes politics look unsavory:

1) Liability-ridden, Bush-connected Dresser got quietly conveyed to Cheney’s Halliburton, at HAL shareholder expense, distancing George W. Bush from the asbestos-mesothelioma scandal and litigation by Dresser retirees, at a time when Cheney was not overtly connected to Bush;

2) Cheney subsequently got the nod to be George W. Bush’s vice-presidential pick; and

3) Once in office, the Bush-Cheney administration provided Halliburton and its business allies with billions of USD worth of federal contracts, while quietly working to delay or to prevent plaintiffs’ lawsuits in U.S. courts.

Halliburton earnings at start of Bush-Cheney administration

The fact that virtually none of this was reported by the Washington political press does not speak well for the political press corps at the time. Contrast the topic above, or any fraction of it, to Al Gore’s switching to brown suits or the canard that Gore claimed to have invented the internet.

A large part of the problem was that insider political reporting back then was dominated by the Washington Post, and most regrettably, the paper’s parent Washington Post Co. had just recently finished buying Kaplan Learning, the giant standardized-testing conglomerate. At a time when the paper was losing money—it still is, as are newspapers in general–the Bush team made explicit overtures to the Post newspaper on the issue of ‘education reform’, which meant billions of dollars’ worth of standardized testing. Both the Bush-brother governors, Jeb Bush in Florida and George W. Bush in Texas, had already increased standardized testing in their respective states. This policy adjustment should have gotten more press scrutiny, given how it flew in the face of both rightwing libertarianism and their state GOPs’ usual attitude toward education.

Al Gore and earth tones

But scrutiny was not the watchword in the 2000 campaign, as we know by now. Candidate Bush got free passes from the Post and from the ensconced press corps—on his drunk driving, his alcoholism, his wife’s having killed another teenager in an automobile accident, his lack of knowledge of national and international affairs, his lack of experience in high office, the inconsistencies and misrepresentations in his military record, the family favors in his career record, the sketchiness of his academic credentials, etc., etc. Meanwhile, Al Gore got taken apart for every trifling detail of clothes or manner. No minutiae went unexamined in regard to Gore; no issue of gravity got the attention it deserved in regard to Bush. And Bush got commendations—especially from the Washington Post—for bringing up the topic of ‘education reform’ or for that matter for bringing up education at all.

Once in office, the administration did get ‘No Child Left Behind’ passed, and the Post Co.’s SEC filings reveal that the push for standardized testing across the nation, in all schools, at all levels–largely what NCLB boils down to—enriched the Post Co. by billions. The company has now officially re-branded itself to the SEC as an education and media company.

None of this was reported by the Post newspaper, which also has gone for years without detailed reporting on continuing asbestos problems in the U.S.

And needless to say, no major publication clued in the public on the Bush-Cheney wish to invade Iraq, already formed when they entered the White House in 2001.

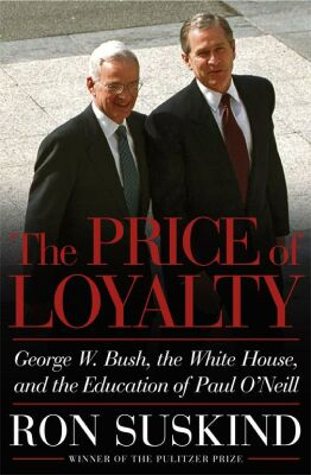

Bush Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill

More later